In Favor of the Shift

In Favor of the Shift

A spring without baseball allows time for reflection about the big issues in life—about what really matters. As a result of this past empty April, I’ve come to a realization: the defensive shift is good for baseball.

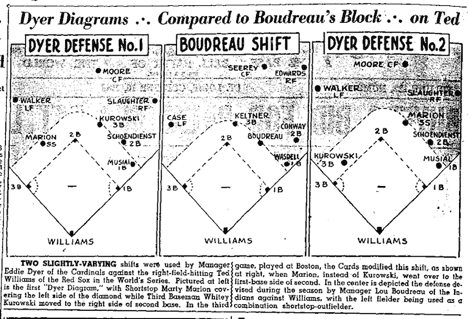

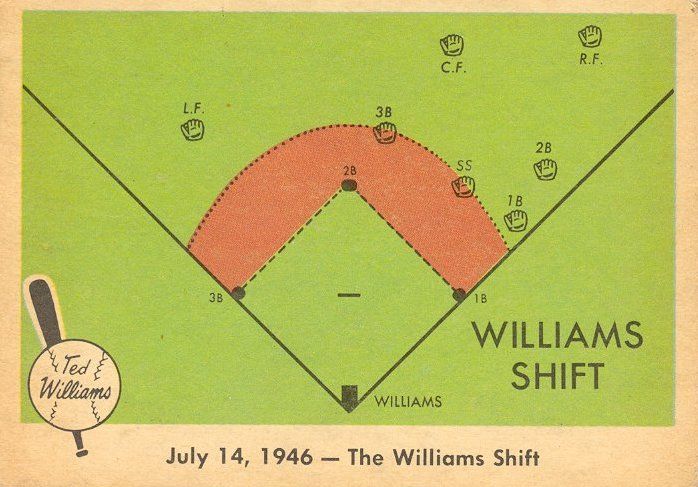

The defensive shift occurs when the defense plays out of its typical alignment. Instead of being distributed across the field relatively evenly, the shift typically involves the third baseman or shortstop moving over to the right side of the field. At times, this shift can become extreme. One of the prime examples being this four-man configuration used by the Los Angeles Dodgers in August of 2014:

Over the past few years, many have decried this defensive tactic, claiming that it is against the spirit of fair play, or puts hitters at too much of a disadvantage. But the shift is not new. While the origin of the shift dates back to the 1920’s, it became well-known as a response to Red Sox legend Ted Williams. He had hit an unheard of .406 in 1941, in 1946 he was hitting .476 headed into May, and opposing teams were desperate to slow him down. Williams was a left-handed pull hitter, making him a candidate for a unique defense.

This approach to Williams found enough success that other teams duplicated it, and the Fleer company even dedicated an entire baseball card to it:

Despite still hitting .348 from 1947 to 1957, Williams had difficulty adjusting to the shift. He hit 1000 of his 1252 ground ball outs in the 1950s to the right-hand side alone.

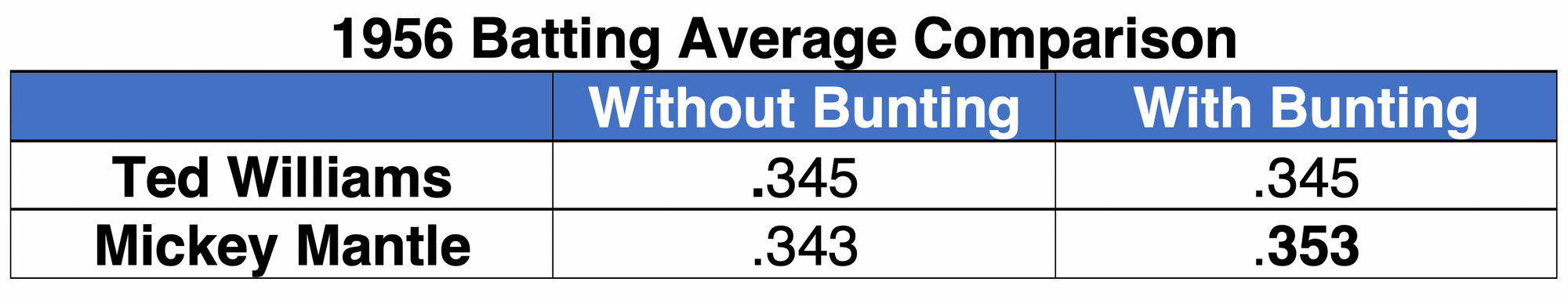

But there are ways to beat the shift, which brings us to Mickey Mantle. He, like Williams, faced the shift during his career with the New York Yankees. Mantle, however, modified his approach to beat the shift in multiple ways: (1) Hit it out of the park: he hit 536 total home runs, good enough for 18th on the all-time list (in his 500th HR, hit in 1956, you can see the shift being used against him.) (2) Hit to the undefended side of the field: Mantle was also a switch hitter, so he could just change sides of the plate and hit to left. (3) Bunt: this is perhaps the most controversial option, but it is one that serves the team if it advances the runner . . . and it won Mantle the Triple Crown (league-best batting average, home run total, and runs-batted-in) in 1956, over none other than Ted Williams himself.

In August of 1956, Mantle was eight games ahead of Babe Ruth’s 60 home run pace. He outdistanced Williams by 28 home runs and 48 RBI, but the batting average was a close contest. Mantle, however, continued to beat the shift by bunting. Over the course of the year, he attempted 21 bunts, the most of his career, and hit safely in 12 of 20 at bats. Here you can see the bunts against the shift and their impact in the Triple Crown race:

Mantle’s innovative approach had won him the Triple Crown, and the Yankees went on to win the World Series in seven games in 1956.

The shift was good for Mantle—it forced him to develop his game in new ways, to develop new skills, and to exploit new opportunities. While Williams allowed his focus to be on the defense, and what was being taken away, Mantle sought new ways to develop his offense.

We’re in a similar position when it comes to identity. We are often focused on what we must prevent rather than on what we can enable; we are continually reacting rather than being proactive in our identity-driven security strategy.

When any shift occurs, our tendency is to hunker down in our safe zone, worrying about what could possibly go wrong. To do more than survive, though—to successfully beat any shift—we should examine our options and adapt; we should diversify and develop our game. We should play offense rather than defense.

Mantle, when asked why he was bunting so much in 1956, was quoted as saying, “When I tried to bunt for a hit, it was because we had to get something started. I figured that winning the pennant was the most important thing of all. Sure, I wanted to break Ruth's record, but not at the expense of winning. ” Like Mantle, we must focus on what the most important thing—what “winning” is for our organizations—and adapt our strategy to achieve that.

Some of these strategy modifications may be home runs: Rethinking the core of identity itself. Reorienting our approach around identity—equipped with adaptive technologies such as machine learning—can flip an organization to offense, proactively providing access to users before they even know that they need it.

Others are the equivalent of switch-hitting: a new perspective that we might not have considered before. Exploring the reuse of new forms of digital identity can open up new long-term opportunities for new markets and partnerships. Implementing privacy controls and securing the data of customers and employees—even before government mandates these controls—can help prove that the organization can be trusted with sensitive data.

Bunting should not be neglected, either. Every small step towards securing resources with identity is a step towards “winning.” Often this means expanding the visibility of an identity program into the dark corners of previously uncontrolled apps.

The shift, then, rather than being a negative for our organizations and for baseball, forces aggression, forces adaptation, forces innovation—it forces the advancement of the game. To ban the shift is to kill opportunity and to settle for the status quo.

The shift is good for baseball. But don’t get me started on the designated hitter.